Would that the origins of these links had partaken of more caffeine before starting the sausage-stuffer…

From the Department of Rats-Leaving-the-Sinking-Ship, online rag The Vulture adds 28 partially disclosed spices to this link concerning the purported state of the "book industry" — spices that apparently didn't reach academics, indie writers/readers, those actually involved with the implicitly-denigrated "genre fiction" (whose sales were implicitly envied), or more than 1km outside of Manhattan. Fact of which these navel-gazers are apparently unaware: The population of Manhattan — about 1.7 million at the most-recent census — was a hair over 2% of the nation's.

From the Department of Rats-Leaving-the-Sinking-Ship, online rag The Vulture adds 28 partially disclosed spices to this link concerning the purported state of the "book industry" — spices that apparently didn't reach academics, indie writers/readers, those actually involved with the implicitly-denigrated "genre fiction" (whose sales were implicitly envied), or more than 1km outside of Manhattan. Fact of which these navel-gazers are apparently unaware: The population of Manhattan — about 1.7 million at the most-recent census — was a hair over 2% of the nation's.

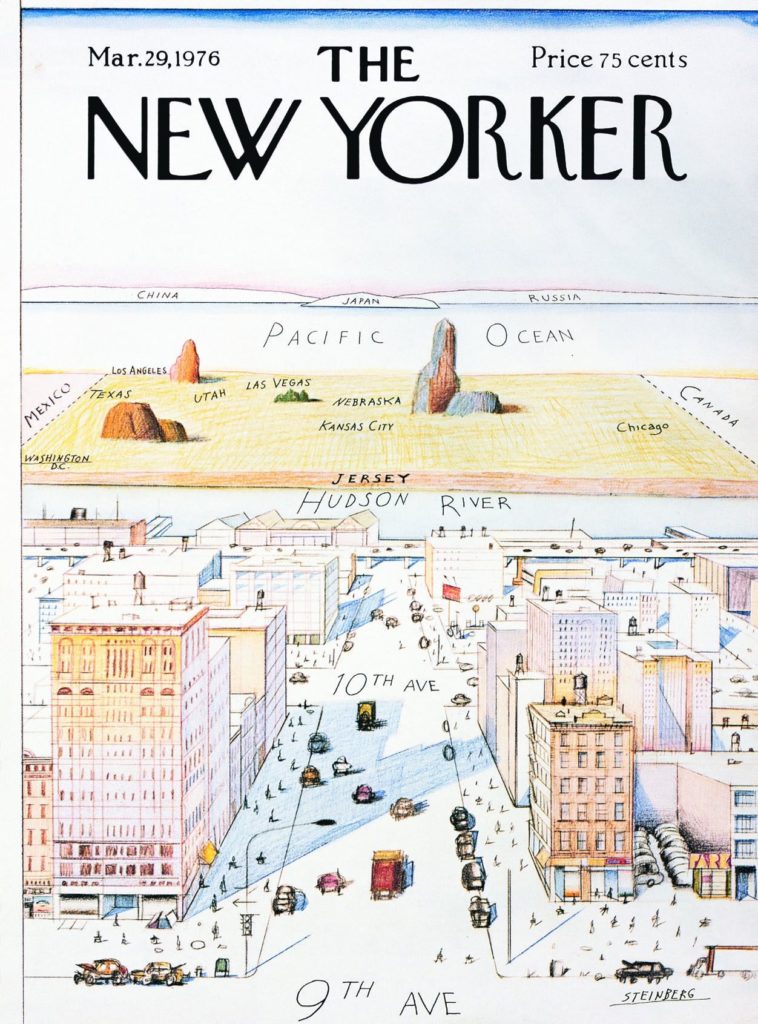

But that last fact is the actual cause of the seeming demise (and general irrelevance) of The New Yorker. It was predictable at the time this notorious cover, and perhaps even as early as the breakup of the Algonquin Roundtable (the desperate attempts of those like F. Scott Fitzgerald to glom onto the nascent H'wood income-and-exposure apparatus should themselves cause reconsideration). If New York had ever been the "center of American culture (for all the right people)" — and Boston and Philadelphia might object, even without getting to the Left Coast — it sure as hell wasn't by 1976, and sure as hell isn't half a century later. More broadly, looking outside the US would have been educational for the author of this… "hagiography" is wrong as to tone, but there really isn't a better thumbnail, blawg-entry-appropriate description.

That these two pieces — and, especially, their subjects — share substantial conceptual difficulties is not coincidental. But at least they're not continuing to struggle with/for/against Straussianism. Or are they?

- The business day is usually considered to begin at 0900 — slackers (the "business day" needs to start with barracks inspection just after sunrise… and, of course, those doing the inspecting had to be up before that). Friday, 02 January 2026, being the first business day of 2026, can you guess how long it took for mutiple dubious appellate copyright decisions to issue? Even on a "one-day work week" due to the way the calendar fell this year?

Around two hours (Pacific time). And were these matters ever dubious…

Let's take the simple one first, although the Ninth Circuit's inexplicable decision to split it into both a precedential and nonprecedential decision makes it look much less simple than it really is. Sedlik v. von Drachenberg, No. [20]24–3367 (9th Cir. 02 Jan 2026) (precedential and nonprecedential decisions issued simultaneously), concerned a simple question wound up in procedural issues resulting primarily from poor advocacy in the District Court: Does a tattoo based on a nonunique (if "iconic") photographic portrait of a deceased individual infringe the photographer's copyright? (Those of you with long memories may recall that we've been here before (first sausage) — regarding a different eminent treatise author, also in snarled procedural posture.) Leaving aside the nonprecedential opinion, which is largely about the plaintiff's procedural shortcomings in the District Court, the real value in the precedential opinion is in the second concurrence — and even it jumps the gun, ignoring Justice Holmes's warning well over a century ago:

It would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of pictorial illustrations, outside of the narrowest and most obvious limits. At the one extreme some works of genius would be sure to miss appreciation. Their very novelty would make them repulsive until the public had learned the new language in which their author spoke. It may be more than doubted, for instance, whether the etchings of Goya or the paintings of Manet would have been sure of protection when seen for the first time. At the other end, copyright would be denied to pictures which appealed to a public less educated than the judge.

Bleistein v. Donaldson Litho. Co., 188 U.S. 239, 251–52 (1903). The danger here is quite obvious, especially given the rejection of the "sweat of the brow" rationale for copyright protection in Feist. To even reach any of these issues, one must determine what parts of Sedlik's photographs are original expression (and credit the "iconic" status of the photographs); then whether there was copying of those parts (which was largely admitted by this defendant); and then whether the defendant has any defenses. And here, the court stumbled rather badly by focusing on a fair use defense — whether properly left to the jury or not — without first considering whose originality is at issue in the "copying" of a portrait that largely omits the background, transforms its medium from photograph to tattoo, and — perhaps most to the point — is far from the only photograph (even similar photograph) of a deceased public figure. And this was not helped by the continued reliance on a line of Ninth Circuit cases that try desperately to evade the guidance of another 1990s Supreme Court copyright opinion — 2Live Crew (a/k/a Campbell). That this panel probably reached the "objectively correct" law-school-textbook result just makes the stumbling prone to falling into someone else's dispute.

- Unfortunately, a very similar is-it-protectable-expression? problem arose in Yonay v. Paramount Pictures Corp., No. [20]24–2897 (9th Cir. 02 Jan 2026). (One ironic similarity: Both Yonay and Sedlik were argued, for losing plaintiffs, by individuals with significant prior records in establishing copyright law.) This time, the court — an entirely different panel of judges — did better in separating "fact" from "expression" for a (IMNSHO bad) film based in part on a nonfiction article; or, rather, the later sequel thereto, and claims by the author of the article that the later sequel infringed the article's copyright, breached the original license, or both.

However, this panel's better copyright analysis was partially overcome by a contract analysis that managed to ignore the context of entertainment-industry contracting in the 1980s and the context-driven "rational expectations" of the parties concerning "life story"-type material. The conclusion may well be correct — the entire text of that contract is not in the opinion, only purported "critical phrases" and an allegation that "nothing in the context of the agreement suggests any reason to depart from" grade-school-grammar analysis of conjunctions. This rather elides away that most entertainment-industry contracts are replete with compound nominatives that embed one or more conjuctions, so hidebound by tradition that a grammatical analysis is positively misleading.† So I'm not convinced: The context of the agreement exactly suggests that simplistic grammar rules probably don't reflect the understanding of the parties, and almost certainly don't resolve the problem of internal definitions that assume familiarity with relevant commercial customs. I seem to recall some discussion of that in 1L Contracts, particularly Rest.(2d) Contracts § 222. Now combine that with the bad writing endemic to entertainment-industry contracts…

- On a seemingly lighter note, the Court of Justice of the European Union attempted recently to discern when a designer's name attached to things he/she/they didn't design is unlawfully deceptive. But maybe this isn't lighter after all, in company with the other sausages on this platter. Nor is it really lighter than the broader questions of "artistic attribution" that it implicates, ranging from trivialities like the darkness of the "painter of light" and dubious employment practices of esteemed local artists that ironically protected his copyright claims to weightier questions like the aphids on the (wilted) flowers in the attic and the propriety of proclaiming "A Film By". I guess the reason this sausage seems lighter is that the CJEU just didn't bulk it out with enough filler.

† As you can well imagine, this can lead to some real headaches while negotiating these agreements. One on which I was a silent/undisclosed consultant about twenty years ago went through twelve iterations of we-remove-a-clause-they-reinsert-it — because the wet-behind-the-ears negotiators for [name of major studio withheld] were working from company boilerplate etched on stone before the Copyright Act of 1978 made their clause both unnecessary and arguably unlawful. They claimed to not have authority to change their well-tested language. We eventually got the removal approved, but still…

The publishing segment of the entertainment industry is no better. Buried in many contracts, even today, are references to "the plates" used to print the books (obsolete since the early 1990s), ipso facto clauses purporting to return all rights to the author upon the publisher's bankruptcy (contra 11 U.S.C. § 362 (1978)), declarations that a freelance (and not commissioned prior to creation) work outside the categories in the Copyright Act § 101 definition is a "work made for hire," and a variety of other problems ranging from definitions of "subordinate rights" made obsolete by both the 1976 Copyright Act and commercial/technological changes since to outright defiance of Supreme Court opinions. How much of this reflects honest disagreement with (what at least I see as) binding law and how much is an attempt to "contract around" that law under some para-Lochner conception is for another time, another few hundred footnotes.