Well, I've run into yet another article demonstrating that the legal academy and profession don't know enough about science to perform reliable "empirical legal studies." And it's a particularly egregious example that fails at multiple points from beginning to end as an experimental design. But I'm not going to name it… because this instance is the third one that I've come across, in three different scholarly areas in which I have both experience representing parties and continued scholarly interest, in the last several weeks. I'm particularly disappointed in this one because the author's acknowledgement footnote thanks someone I would have expected to object to these flaws, but that's a secondary process flaw that is subordinate to the fundamental problem:

Lawyers not only don't know what "replicable evidence" is — they don't care so long as they have something to feed into a black box that has the Authority of Statistical Manipulation to support a preconceived ideological or doctrinal viewpoint.

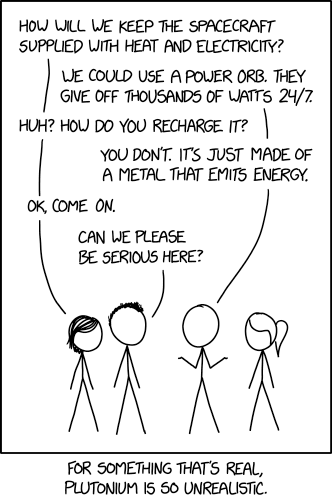

And they can get away with it precisely because the profession's leadership (including, but far from limited to, both academia and the judiciary) is so ignorant concerning scientific and mathematical method and proof. So ignorant that as a whole, it doesn't understand either this cartoon or its implications. Obviously, my misspent youth has caught up with me.

And they can get away with it precisely because the profession's leadership (including, but far from limited to, both academia and the judiciary) is so ignorant concerning scientific and mathematical method and proof. So ignorant that as a whole, it doesn't understand either this cartoon or its implications. Obviously, my misspent youth has caught up with me.

Not in the order that they should occur to a researcher, nor in the order that they should be dealt with, but in the order that they're easiest to describe, here are the critical problems shared by all three of these unnamed works (all accepted for publication, one at a "top ten"ish law journal and one at a "peer-reviewed" law journal):

- The data set consists solely of reported decisions. This is inherently a fundamentally distorted data set rife with problems. To begin with, it is functionally the equivalent of determining the public's acceptance of civil rights for negroes in 1962 by setting up a table in an upper-middle-class residential district between 4:30 and 6:30pm, manned solely by white men wearing suits (and locally appropriate hats) speaking in the local accent… and only asking the question of similarly dressed white men who walk up to the table, and recording only an unnuanced yes-or-no answer.

As ridiculously obvious and obviously ridiculous as that seems, it understates the self-selection problem with relying upon "reported decisions" for anything other than what reported decisions themselves say. And it's not just the most-obvious problems with "no women" and "no minorities," either — consider the disabled who don't walk (or are embarassed by a stutter and don't speak), the shift workers and at-home workers who don't pass by during that time window, the idle rich (and, more egregiously, the unemployed), the nonnative speakers of English, the nonconformist self-made millionaire who hates hats. The fundamental problem with relying upon "reported decisions" for one's data set is that the economic circumstances of the respective parties, and therefore their ability to get into a court that issues a reported decision, are completely independent of the merits or the representativeness of wider context.

More subtly, some circuits (and state courts) have policies discouraging reported decisions — "cultural," official, or de facto. I'm thinking specifically of the federal Fourth Circuit here, such as this well-taken reservation. Whether or not one agrees with that "culture" for any reason, it strongly undermines the validity of any study that restricts itself to "reported decisions."

In some fields, restricting the data set to "reported decisions" has another, more disturbing effect on data integrity: Some courts obstinately refuse to reconsider their past decisions in the light of new authority (whether simply a statutory change or even, in some instances, intervening Supreme Court authority). A per curiam decision earlier this week demonstrated that the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals doesn't, umm, understand the Supremacy Clause (PDF) (being as polite as I can because my only understanding of the facts comes from those portions summarized in the respective opinions; see next point below). This is an obvious example; the Second Circuit's refusal to engage with the inability of its judge-made work-for-hire interpretations under the Copyright Act of 1909 to satisfy the definition stated in the text of the Copyright Act of 1976 is less obvious, but more central to my particular concerns. Further, it's never clear from these studies reflecting "reported decisions" how decisions that are later overturned, abrogated, or abandoned are treated — and that matters a lot (see below).

- Which leads directly into the next point: The presumption that reported opinions are accurately reporting the relevant facts, let alone accurately characterizing them after being filtered through at least two sets of attorneys who probably don't have all that much understanding of the distinction between "admissible evidence" and "factual knowledge that influences parties' decisions and actions." To use an obvious example, one party's years-afterward recollection of verbal promises made that induced agreement to a written contract that includes the kind of integration clause taught to first-year law students aren't going to make it into the record that is behind a reported decision, not even in the trial court when trial courts' decisions are reported. Not even — and perhaps especially — when the other side admits to its own counsel that those representations were made (or different ones with similar weight) and then denies it during a deposition. <SARCASM> But that never happens. </SARCASM> A motion in limine will successfully keep that "fact" out of the record and therefore outside the consideration for a "reported decision."

Some contextual issues that really matter also fall inside this problem, especially relating to allegedly derivative works. The Cariou fiasco, and the more-general problem of "appropriation art" and noncreator-made derivative works, depends upon an understanding of artistic process that is unique to individual circumstances… and that is precisely what is not supposed to be at the core of reported decisions. Reported decisions are supposed to make generally applicable legal doctrine clear and known to the public in a manner that will enable the public to comport its conduct to the requirements of the law. This is particularly problematic for the "transformative use" doctrine because — leaving aside the insoluble and nongeneralizable ex post / ex ante (a/k/a "retconning" and "post hoc rationalization") flaw inherent in the doctrine — there is no universal "creative process" to which it can be applied. Even the slightest modification of the context in Cariou demonstrates this: How would one evaluate this if we were dealing not with photographs, but with painted portraits? How about sculpted likenesses (before considering whether that's in clay or in marble or in collected objects bound together)?

This is an institutional problem inherent in reported decisions: The presumption of judicial (and, more generally, lawyerly) competence. I can only repeat Justice Holmes's imprecation regarding the seemingly lawyerly concept of "originality."

It would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of pictorial illustrations, outside of the narrowest and most obvious limits. At the one extreme some works of genius would be sure to miss appreciation. Their very novelty would make them repulsive until the public had learned the new language in which their author spoke. It may be more than doubted, for instance, whether the etchings of Goya or the paintings of Manet would have been sure of protection when seen for the first time. At the other end, copyright would be denied to pictures which appealed to a public less educated than the judge. Yet if they command the interest of any public, they have a commercial value — it would be bold to say that they have not an aesthetic and educational value — and the taste of any public is not to be treated with contempt. It is an ultimate fact for the moment, whatever may be our hopes for a change. That these pictures had their worth and their success is sufficiently shown by the desire to reproduce them without regard to the plaintiffs' rights. We are of opinion that there was evidence that the plaintiffs have rights entitled to the protection of the law.

Bleistein v. Donaldson Litho. Co., 188 U.S. 239, 251-52 (1903) (internal citation omitted). And it's even worse in many other less-lawyerly areas, such as "what does a DNA match really mean" (thank you ever so much, Justice Scalia) and even more-lawyerly ones like superiority of class-action litigation as a means to resolve disputes, or the cost-benefit factors behind a policy "favoring" arbitration (which is based almost entirely upon a leap of faith expressed in a judicial opinion).

- Then there's a deeper, methodological problem: Are the particular statistical tools applied to the data set in question valid in the domain of that data set? Leaving aside the "empirical versus epidemiological" debate (and the intentional absence of controls), consider two questions raised by the presentation of a different article. First, are we dealing with a two-tailed, a multi-tailed, or an indeterminate-tailed decision tree that must emanate from that data set? In law, the assumption that everything is "two-tailed" dominates judicial decisionmaking: "Guilty" or "not guilty," "liable" or "not liable," "reversible error" or "not reversible error." Sometimes, however, degree matters as much as kind, and I don't mean just "murder in the second degree." Any time one sees a balancing test or multifactored inquiry, one must be suspicious of binary outcomes. "Fair use" (17 U.S.C. § 107) is an obvious example; so is "piercing the corporate veil" (e.g., under Alabama law (and this case remains valid)). Many statistical tools, however, are only valid for two-tailed decision trees, such as the so-called "t test" — and using them outside their boundary conditions is comparable to using the handle of a screwdriver in place of a hammer, or more often to using a hammer to try to drive in a screw. With enough force, it can sorta work… but usually ends up damaging things further and making rather impermanent connections.

Second, there's the more subtle problem of internal data integrity. When one is dealing with judicial decisions, the most-obvious factor is the comparative quality not of the facts, the parties, or justice, but of the lawyers. Too often — especially in areas outside the experience or expertise of the specific judge(s) actually hearing the matter — "persuasiveness" issues get too much weight, resulting in sampling from non-normal distributions with unequal variances. This isn't precisely a consequence of the "economic status of the parties" issue in point 1 above; sometimes really exceptional counsel represents the "less well-endowed" side, such as in almost all significant civil-rights cases. But that is far less correlated with the true merits of claims and defenses than it might seem.

- Last, and most lawyerly of all, there's the influence of pure civil procedure upon the doctrinal result — and this problem is almost always neglected in statistical studies of case outcomes, whether just reported decisions, including "nonreported" decisions, including "resolution of cases actually filed," or Cthulhu-forbid consideration of nonjudicial dispute resolution (whether administrative or arbitral). Consider, for example, a reported decision that denies summary judgment because there remains a material fact in dispute. The standard here is that there was enough evidence presented to avoid summary judgment — that some weighing of evidence would be required by a finder of fact at trial. Cf. Fed. R. Civ. Proc. 56.

There are two pitfalls here. One is an improper presentation of the motion or opposition that — despite its underlying merit — results in an adverse finding. When I was practicing in Chicago, I observed (not in any of my own cases!) that failures to satisfy the exacting "statements of fact and evidence" requirements of (former) Local Rules 12(m) and 12(n) in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois were frequent causes for adverse decisions on summary judgment… because a failure to follow all of the purely presentational aspects of those rules resulted in a finding that the opposing party's factual assertion was deemed admitted for the purpose of that summary judgment motion. Cf., e.g., Bell, Boyd & Lloyd v. Tapy, 896 F.2d 1101, 1102–04(7th Cir. 1990) (failure to meet formatted-opposition requirements of Rules 12(m) and 12(n) affirms summary judgment, even though "Standing alone, Tapy's affidavit would be sufficient to create genuine issues of material fact"). Aside: I fully support Rules 12(m) and 12(n) and wish that they had been formally adopted, including required forms, into the nationwide federal rules… but it's impossible to deny that they place a significant burden on pro se parties and inexperienced counsel. That is, indeed, my point.

The second is more subtle, and relates to a judge's understandable tendency toward Dunning-Kruger fallacies (abstract only). As a group, judges issuing reported decisions are smarter than the average bear — they've got graduate degrees and passed the bar exam, which makes them smarter in some realms of knowledge than Airman Basic Slugworth (a barely-graduated-from-high-school kid, despite his undoubted auto-mechanic and woodland-survival skillsets). The difficulty, parallel to the problem noted by Justice Holmes and quoted above, is that judges are not very good at acknowledging that failure to really comprehend the details of complex factual and doctrinal contexts impairs the accuracy of decisionmaking — and, more to the point, decisionmaking that makes or alters doctrine. Judge Hand's inability to recognize his lack of mathematical sophistication in attempting to extend the so-called "Hand Formula" of Carroll Towing from a particular narrow instance to a universal rule — without even inquiring into whether the variables B, P, and/or L were independent, or continuous, scalar, or even had compatible units, let alone whether his purely-additive meme related to a stable function surface — is just a particularly obvious example. Returning to summary judgment for a moment, though, lays bare a potential worse alternative: Throwing complex decisions of fact into the hands of a far-less-educated-on-average-than-is-the-judge jury, and adding the spectre of not just "lawyerly persuasiveness" but "expert-witness persuasiveness" to the boiling-over pot.

For all of these reasons, relying upon "reported decisions" as the data set from which to draw defensible and replicable conclusions not as to judicial behavior, but as to doctrine or merit or even underlying factual circumstances, is indefensible and inappropriate. Statistical analysis of invalid data sets just isn't helpful… especially when the decision to "publish" or not is nonobjective.